JOHN CORNU

NOVEMBER 20, 2009 - JANUARY 23, 2010Press release

Tant que les heures Passent, Part III

For the third and final stage of the project Tant que les heures passent, John Cornu sets out to reinitiate

works created for the occasion of his residencies in Lyon5 (France), then in Quebec City6 (Canada) and now

finally in Brussels. On three different occasions and in three places, the artist has built the framework of a

modular exhibition that has unfurled gradually, as a result of these varying geographies.

In Brussels, the exhibition retraces the steps taken on an artistic voyage that has sought contemporary forms

of

ruin and blindness. Taking up a theme much favoured by the romantics, the artist sets out to reformulate its

signs according to the codes of an art that is both minimal and conceptual. On the face of it, these two

genres

are diametrically opposed in every way, one favouring an exaggerated sentimentalism, the omnipresence of the

sub- jective and the elegy of desolation, with the other refusing the excesses of expressionism and laying

claim

to a certain neutrality.

And yet it is precisely in a continual flux between these antagonistic forces that John Cornu’s work lies. In

place of a conception of time as something linear, leading inexorably towards decline, the artist opts for a

cyclical approach that reminds us how often history repeats itself in a world suf- fering from chronic

blindness7. Despite this, the exhibition is not limited to the helpless observation of an obsolete world: the

artist opens up the field of what is possible by overcoming, through the poetics of the ruin, the apocalyptic

conception of which it carries merely the appearance.

In Sonatine, whose title is borrowed from the film by Takeshi Kitano (sub- titled “Mortal melody”) the artist

sets out a veritable musical and visual composition, replacing the fluorescent lights of the exhibition space

with worn-out strip lights that have been thrown away. Out of a principle of economy (not to mention ecology),

the artist reveals the artistic potential of these lights destined for destruction, but which here are given

the

time to function until they go out completely. Paradoxically, the artist delegates what is a random and

evolving

orchestration to industrial “nature”, shifting our view of something that could be considered dysfunctional by

a

consu- merist society used to endlessly renewing products well before they are utterly spent. Whereas in Lyon

the installation unfurled across the whole of the exhibition space, in Brussels the work finds itself confined

to a single entity, flashing like an emergency Morse code that remind us, perhaps, of the declining heritage

of

a century of enlightenment on which the basis of democratic society has been built.

As with numerous works by John Cornu, Sonatine invites us to learn to look more closely, beyond what is

immediately visible. Thus, among the works created in Quebec, the artist entrusted the making of artists’

stretchers (Tirésias8) to a partially-sighted woodworker who suffers from blindness as a result of a

degenerative disease. At first glance, the works displayed barely differed from the industrial frames on sale

in

art supply shops, had the artist not chosen to show them alongside a series of interviews under- taken with

the

craftsman during the making of these pieces. In this series of “hollow paintings”, which can be seen only by

means of their structure, the artist places the viewer on the same plane as the blind person, thus inviting us

to project our own images onto the empty screen.

Likewise, with the photographic series La pluie qui tombe [Falling rain], the artist attempts to capture an

impossible image. Taken during the night using a flash, these photographs of rain only manage to capture a

constella- tion of planets that remind us to what extent the technological capabilities of photography are

illusory when it comes to creating an objective reality. In The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical

Reproduction, Walter Benjamin had already distinguished “what we see from what we look at”, at a time when his

contemporaries were certain that this new process would end the separation of the real world from its

representation. Since then, we have recognised that the photographic image, when presented out of context, can

be misleading. As proof, the artist has taken one of the emblematic images of September 11th from the

newspaper

Libération depicting a fal- ling man who has thrown himself from a window of the burning towers. By carrying

out

a reframing of the image and rotating it 90 degrees, John Cornu has transformed what is an icon of those

terrible events into a modern version of a recumbent funerary statue. It is as if he has been able to perform

an

acceleration of time, thereby making the final result of the action visible.

In this game of appearances, the artist enjoys the transmutation of forms from one material to another: thus

steel girders, used in architecture to bear structural loads, have been reproduced in glass (Sibylline).

Having

become transparent and particularly fragile, they can only be seen as vestiges of a bygone modernity. In Greek

mythology, the Sybil symbolises primitive revelation. This gives her the power to prophesy in an enigmatic,

myste- rious and often obscure form. Adjectivally, the term is often used to define an utterance with a double

meaning, a possible formulation of which can be seen here. Between observation and prophesy, the exhibition

carves out a relationship with time and with the complexity of history where nothing is ever taken for

granted.

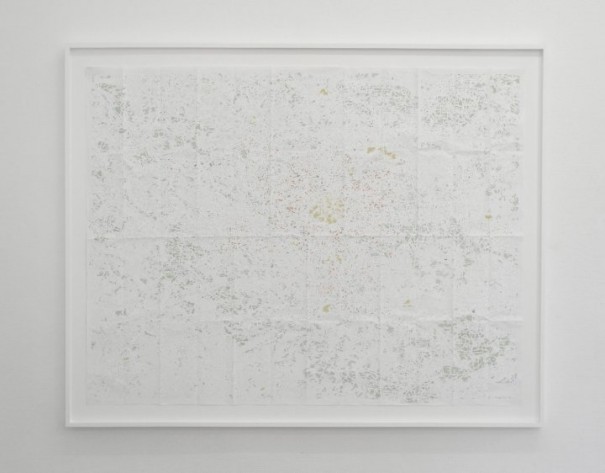

As if better to represent the course taken from one residency to the other, the artist sets out to follow the

routes on road atlases by progressively obli- terating them with Tipp-ex. With this gesture, consisting as

much

of erasing as of drawing, topography becomes a form of abstract landscape, remin- ding us, if necessary, that

the demarcation of territories is fluid and has forever been the predominant issue in global conflicts. It is

doubtless not coincidental that this project has unfurled across three countries that share a common language,

which nonetheless differs subtly in each, reflecting a work whose final form is always adjusted by the display

space. By moving his studio to keep up with the stages of the exhibition, the artist redefines a style of

contextualised art that, unlike its predecessors, is governed less by an “in situ” aesthetic than by a

“situated” logic, where the works are temporarily adapted to the site.

Born in 1976, John Cornu lives in Paris. His work has been shown at numerous solo and group exhibitions: as

part

of the Lyon Biennial of Contemporary Art, at La Chambre Blanche in Quebec City (Canada), at the Villa Savoye

(Poissy), at La maison rouge – Fondation Antoine de Galbert, the Point éphémère, and the Musée Picasso as part

of Nuit blanche 2007 (Paris), at the Générale en Manufacture (Sèvres), at Circuit and 1m3 in Lausanne

(Switzerland) and at the Niederanven Culturel Center (Luxembourg).

Christian Alandete

Translation: James Curwen

Video

John Cornu

Sonatine (Mélodie Mortelle), 2009

Old and used fluorescent tube, micros and amplis

Variable dimensions

Exhibition’s view « Tant que les heures passent, Part III »,

Ricou Gallery, Brussels

© John Cornu

Courtesy the artist and Ricou Gallery

Views

Wood and acrylic

Various dimensions

Unique piece

Wood and acrylic

Various dimensions

Wood, glas and glue

Various dimensions

Wood and brochures

100 x 81 cm

Newspaper "Libération" - 11 september 1009 and marie-louise

41 x 64 cm

Typp-ex on road map

113 x 145 cm

Neon, micro and amplis

Various dimensions

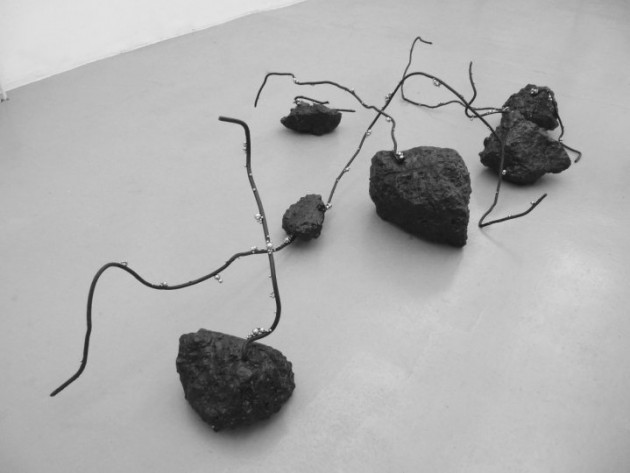

Concrete, magnetic beads, glycéro paint

Various dimensions

Detail

Detail

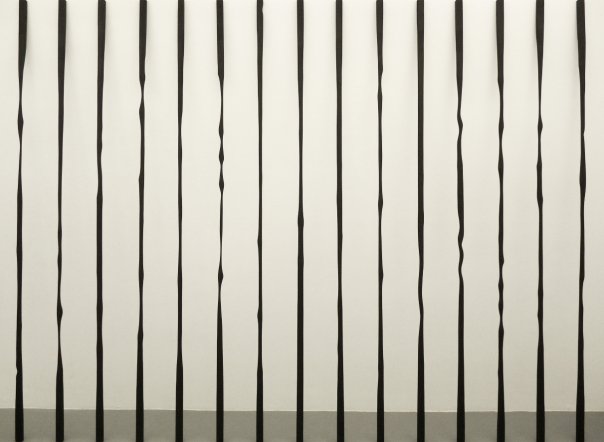

Wood and acrylic

5 x 3 x 200 cm

Wood and acrylic

5 x 3 x 200 cm

Unique piece

b/w photography on aluminium

Unique piece in a limited serie

b/w photography on aluminium

Unique piece in a limited serie

b/w photography on aluminium

Unique piece in a limited serie

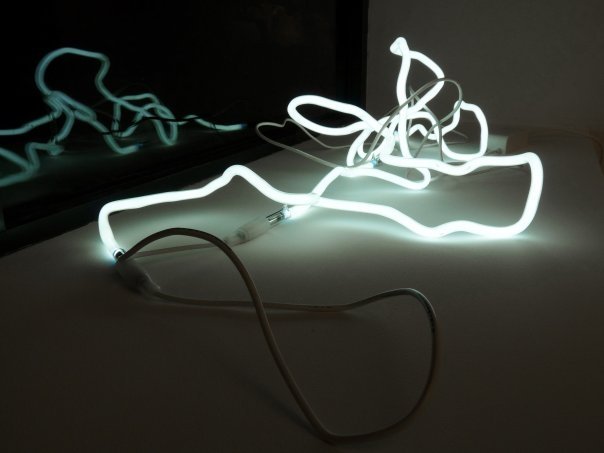

White neon, cables and transformers

Various dimensions

Unique piece